Dropping The D

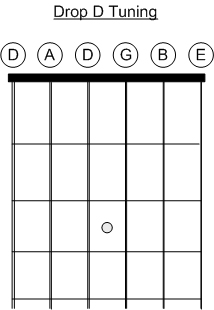

One of the most common alternate tunings in rock music is the “Drop D” tuning. The Drop D gets it’s name because you simply drop the low E string to D and you are good to go. Jimmy Page was known to explore lots of different tunings in the Zeppelin catalogue, but to my knowledge only two are in Drop D: Moby Dick, and Ten Years Gone. (He has several others in “Double Drop D” which also drops the high E string to D). See Fig. 1. for Drop D tuning.

As crazy as it sounds, there are videos on YouTube of guys not only playing Ten Years Gone in standard tuning, but also teaching it in standard tuning. This isn’t a case of making the choice to transpose the song to fit standard tuning – they’re just playing it wrong and are missing out on all that Drop D goodness. That low D note is part of the dark majesty that makes Ten Years Gone such a standout composition so it’s a shame when guys overlook it.

When you are learning a song off the record, get used to zeroing in on the lowest note being played and compare it to your low E string. In standard Tuning (A=440) that note is often obviously the low E. If the note you are hearing is lower than the E consider two possibilities: that it’s in Drop D tuning, or that the guitar might be tuned a half step down (a very common thing with some guitar players). Just ask yourself: Am I hearing D or am I hearing E♭?

You can also get tripped up while reading transcriptions or tab in magazines or on the net. Most, if not all, tabs will specify a tuning or have a tuning legend at the top of the transcription. Make sure you check. That’s a pro-tip: always check the transcription/tab for notes on tuning.

More Guitar Related Technical Detail

When setting up your guitar to play in Drop D there are a few technical things to consider. A guitar is always looking for equilibrium – a balance between string tension and neck relief. Any changes you make to the instrument with respect to tension, (either from the strings or the truss rod, or even things like bridge height or saddles) will cause changes to this equilibrium. On a fixed or hard-tail bridge, dropping the E string to a D doesn’t necessarily cause the guitar to suddenly play different or lose it’s immediate equilibrium, but it can cause subtle changes over time that can eventually lead to changes in the neck relief and affect your action or your intonation. For this reason, many guys who play in Drop D will have guitars specifically setup for Drop D.

If you have a tremolo bridge things can be a little more complicated.

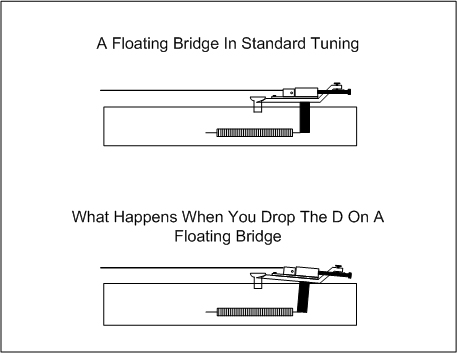

If your tremolo is flush mounted to the body of the guitar, dropping the D is a little easier because the lessening of tension that results from loosening the E string to D is mitigated by the fact that the bridge sits flush to the body of the guitar. A typical strat style tremolo is setup this way and you wont experience too many drawbacks in terms of tuning stability or intonation issues from dropping the D and you can treat it much the same way as you would a hard-tail. This changes if your tremolo is a locking style floating tremolo. Dropping the D lessens the forward tension of the strings on the bridge causing it to angle backwards as the springs exert relatively higher force and pull the back of the bridge into the cavity of the guitar body. This changes both the position (back to front) and height at which the string leaves the bridge saddles and results in changes in tuning for all strings. You will have to unlock your locking nut and retune the whole guitar from scratch. Even with the guitar re-tuned you’ll notice a slight backward drop on the bridge (see Fig. 2. for an exaggerated depiction ) because you’ve now changed the equilibrium point of tension between the strings and the springs. If you are just playing around for a bit in Drop D this won’t be too big a deal. You might experience some small but immediate changes in intonation or string action, but most of these things you will be able to live with if it’s for a single song in a set or a single practice session. If it’s for longer, or if you are doing something like recording, it might bother you more.

This doesn’t mean you can’t or shouldn’t do it – it just means that your guitar may experience some issues that will affect the tuning stability and/or the intonation beyond your comfort level when you Drop the D. You can mitigate this by using various tremolo blocking devices that lock the bridge in place prior to dropping the D. Products like the Tremol-No™, or a Tremolo Stopper are great for this.

Another handy device is the D-Tuna for Floyd Rose style bridges that was designed and marketed by EVH (Eddie Van Halen). The D-Tuna doesn’t necessarily compensate for the tilt back of the bridge but it does allow you to quickly alternate between standard and dropped D tuning on the fly without having to mess around with your locking nut so you can drop it into D for that one song in your set and pop it back without hassle. It works better with flush mounted Floyds, but will work with floating Floyd Rose bridges as well.

If you have a Floating Floyd Rose guitar and you are considering recording or playing in Drop D for a period of time, you may need to consider allowing the guitar to find its new equilibrium point as the neck starts to adjust to the changes – often requiring a full new setup in Drop D. Every guitar is different in this regard with respect to how dramatic these changes are. You will be the best to judge when that is required.

Have Fun With The D

There lots of good reasons to experiment with alternate tunings, and Drop D is the easiest one to start with for any guitar player. Play around with it for a while and watch how that extra low D changes how and what you play. Guitar players get locked into playing in certain keys because of the way the guitar is strung and how it is voiced, and Drop D can open up a whole new worlds and break you out of familiar ruts and patterns so it is really worth checking out. Have fun with it.

Feature Image Credit: iDrops by Nikk, via flickr, CC BY 2.0